As described in the previous chapter, a digital enterprise is defined by its more intimate methods of communicating with customers, employees and business partners through the use of digital media and especially the use of data. This approach needs, as well as allows, new processes and business models. Therefore, the main differentiating factors between classical and digital enterprises are their access to and systematic application of new information and communication technologies throughout the entire value chain. Hence IT becomes the core of the value chain.

Business models give answers to questions regarding the course a business takes to reach its main objective – making money.[1] Accordingly, it is surprising that a universally recognised definition of the ‘business model’ concept is absent from common literature. Timmers,[2] Weill and Vitale[3] and Osterwalder and Pigneur[4] reveal respectively different emphases and attributes in their definitions.

The objective of an enterprise is realised either through precisely one business model (mainly found in small start-ups) or through the use of numerous business models aimed at achieving the enterprise’s objectives and the value propositions resulting from them.

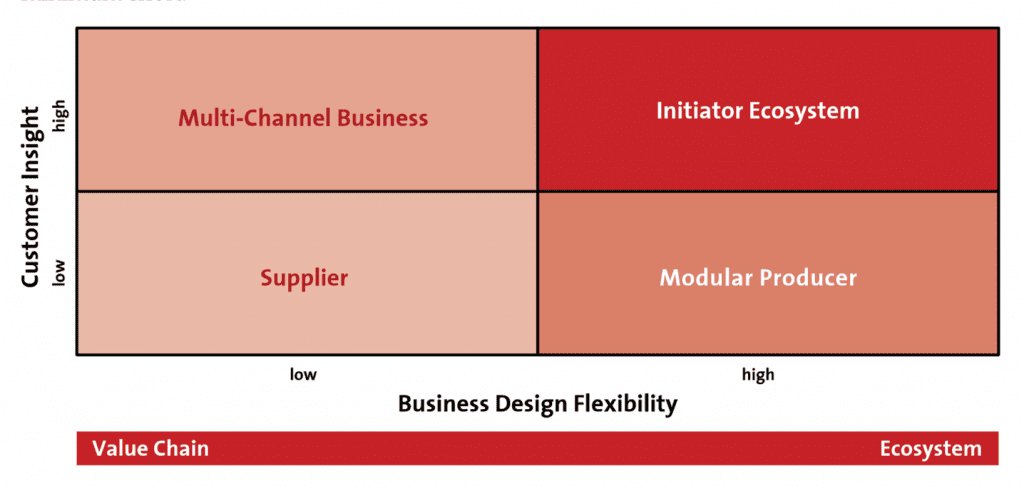

Also missing in published literature is a universally recognised classification of business models. This book uses the work of Weill and Woerner as a basis to discuss digital business models.[5] Weill and Woerner principally consider two basic dimensions: business design flexibility (the degree of flexibility in a business model) and customer insight (degree of knowledge about the customer) to establish essential relevance to the customer.

The business design flexibility dimension ranges from an entire value chain that an enterprise wants to control autonomously, to an ecosystem as a platform on which different stakeholders in the value chain operate cooperatively. The key feature here is the depth of in-house production with respect to the total value chain.

Enterprises with a greater depth of in-house production tend to have less flexibility in the layout of their business models, whereas a shallower depth of in-house production typically offers greater flexibility – flexibility that allows for an adjustment or change of business models with minimum effort.

Customer insight addresses the manner in which an enterprise is acquainted with its customers. This includes whether or not gathering information about a customer’s significant life stages is possible and who is in charge of customer relations. Enterprises that own this sort of information and also manage their own customer relations have a high degree of customer insight.

The figure above (Weill and Woerner)[6] shows the resulting matrix and the equivalent four different business models for digital enterprises. The Supplier business model is the classic producer of products covering nearly the entire value chain. A third party carries out the distribution of products. Under these circumstances, enterprises do not know their end customers well and the business is less flexible. Both the insurance sector, with its agency model, and the automotive supplier industry are examples of this business model. Conversely, the business model of the Modular Producer offers modular products and services that can be integrated into nearly every sector.

This business supports parts of the value chain of other businesses. As a result of these ‘atomic’ products and services, enterprises that use this business model have a very high degree of flexibility in the layout of their businesses. However, they lack information about their end customer: PayPal, Facebook Login and Google ID are good examples of this business model.

The Multi-Channel Business model requires multi-channel implementation (distribution and products) in order to deal with the frequent changes between the online and offline activities through an integrated value chain.

Each enterprise knows its customers and their life circumstances very well. Good examples of this can be found in the banking industry. Younger or more progressive enterprises, on the other hand, have the tendency to establish the business model of an Initiator Ecosystem. Famous examples of this are Apple, Amazon and Google. They offer an integrated platform to target customers who have the ability to integrate themselves into their platform. They are careful about featuring the ‘right’ partner on their platform to meet their customers’ needs. As initiator and caretaker of this ecosystem, these enterprises nurture their customer relations very well and have deep insight on their life circumstances.

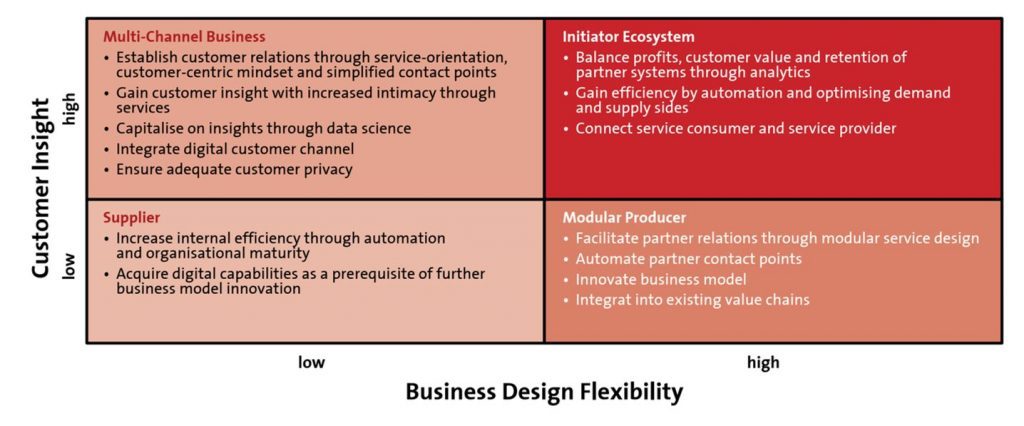

Digitalisation specifically supports each of the different business model types, as the figure above indicates.

Enterprises must classify their business models and derive the respective activities to acquire the necessary capabilities, and systematically apply them to modernise their business.

_____

[1] Sensler, C., Grimm, T.: ‘Business Enterprise Architecture. Praxishandbuch zur digitalen Transformation in Unternehmen’, entwickler.press, 2015.

[2] Timmers, P.: ‘Business models for electronic markets’, Electronic Markets, Vol. 8, Iss. 2, 1998.

[3] Weill, P., Vitale, M.: ‘Place to Space: Migrating to eBusiness Models’, Harvard Business Review Press, 2001.

[4] Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y.: ‘Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers’, John Wiley & Sons, 2010.

[5] Weill, P., Woerner, S. L.: ‘Thriving in an increasingly digital ecosystem’, MIT Sloan Management Review, Vol. 56, Iss. 4, 2015.

[6] Weill, P., Woerner, S. L.: ‘Thriving in an increasingly digital ecosystem’, MIT Sloan Management Review, Vol. 56, Iss. 4, 2015.