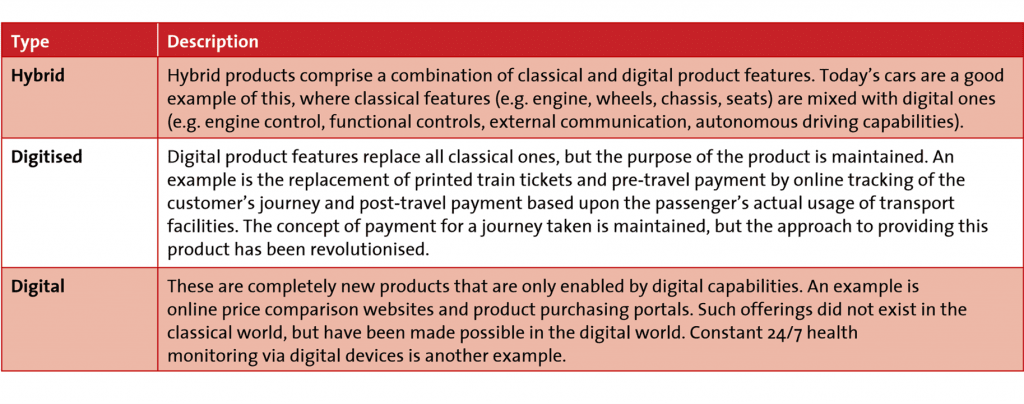

This section defines what we mean by ‘digital products’. The digital product strategy of an enterprise defines the degree of digitalisation a product is subject to, i.e., the extent to which digital features are incorporated into the product. Based on the degree to which digital features have been incorporated into them, products are divided into three principal categories.

Generally speaking, intangible products (e.g., a bank account) lend themselves to complete digitalisation, while tangible products (e.g., hardware produced in a manufacturing facility) cannot be virtualised but instead augmented with digital features. Examples of the latter would be the instantaneous usage of available product data (internal and external) to determine the state of the product and react automatically to changes via new feedback loops.

It may also be possible to leverage the analysis of big data at the time of customer contact to interact with the customer in an intelligent way.

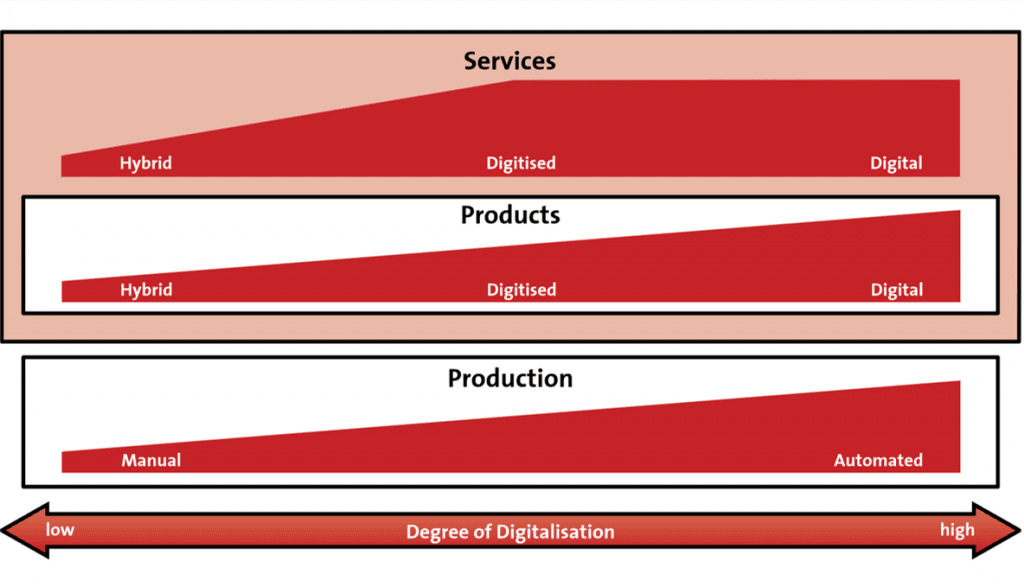

Given the more intangible nature of services, another important digital trend is the potential for a much more comprehensive augmentation of products with services. Services can be embedded into the context of many classical products – e.g., predictive maintenance initiated or even executed by the product itself. Access to such product-related services can be fully digitised, with the customer using digital devices to seamlessly access them and incorporate them into day-to-day life. It is clear that the degree of digitalisation of the product-supporting service can vary significantly from the degree of digitalisation of the product itself. This is due to potentially different degrees of intangibility of products and their supporting services.

The digitalisation of order fulfilment can also vary: it can combine traditional and digitised (and hence mostly automated).[1] Thus we can have a fully digitised product combined with a manual service, and a fully tangible product with an automated, digital service. One example would be electronic train tickets supported by the classic service desk. Another example would be a physical part of a device with an imprinted QR code (quick response code) to access the description of the part or issue an automated replacement order.

The application of artificial intelligence is an important emerging trend for more advanced, fully automated digital services.

Imagine in the second example that an algorithm detects how the device is currently used and offers usage-specific functionality behind the QR code.

Regardless of the nature of the products and the services as perceived by the customer, the delivery of such products and services can also have varying degrees of digitalisation. Differing levels of digitalisation translate into various degrees of process automation, as in the context of the automation of production, the automation of the enterprise’s response to service requests, and the automation of product feature adaptation to demand (e.g., adapted driving behaviour of the car or on-demand delivery).

The digital strategy of B2B (business to business) enterprises must take into account the digital strategy of their customers; that is, the demand for digitalisation stemming from the customer’s own degree of digitalisation.

The supplier’s product must be able to connect suitably to the customer’s potentially more digital environment. The supplier must also be aware of the changes in demand for digital interfaces. Digital capabilities are driving the adoption of feedback processes between an enterprise and its suppliers with the expectation that the suppliers will react. This fact is even more evident once the enterprise is a member of a close-knit digital ecosystem.

Looking again at the example above of the device with an imprinted QR code: Enterprise A produces physical devices, which Enterprise B uses as part of its production chain. If Enterprise B expects fully automated monitoring, exception handling and corrective action triggering in managing its production and aftersales chain, it will rely on providers like Enterprise A for devices that can support such automation and provide the appropriate interfaces in their aftersales customer interaction. Enterprise A will feel this competitive pressure and must constantly monitor its customers’ expectations, and seamlessly integrate processes running in its customers’ environments into its own internal processes.

_____

[1] Chui M., Manyika J., Miremadi M.: ‘Where machines could replace humans – and where they can’t (yet)’, McKinsey, 2016.