Companies have their limitations in the task of coping with growth. They pay for additional growth with inefficiency, with the consequence that profits and sales can no longer be easily increased by sheer growth. In the digital age, large companies are challenged to break through this limit by more effective means of communication, improved data management and automated processes, while digital platforms enable smaller companies to organise themselves into networks to jointly implement large projects.

Historically, ancient and medieval enterprises usually consisted of only a few people. Rapid growth began with the Industrial Revolution, during which the first industrial companies with several hundred employees emerged. The size of enterprises rose steadily in the following decades,[1] many exceeding hundreds of thousands of employees. As transport and communication technologies became available in the middle of the twentieth century, companies grew into real giants.

One reason for the growth is the strategy of utilising new employees, locations and products to quantitatively expand the business.

But equally important is the tendency for the research and development (R&D) costs of complex modern products (such as cars, mobile phones or medicines) to be viable only if these products are marketed on a global scale. For example, the current cost to develop a new car model is higher than one billion US dollars; very large sales volumes become a necessity to recover such great R&D costs.

Generally, a huge company size is not bad per se. However, many enterprises have reached a size such that additional growth generates an exponential increase in complexity.

For example, adding a second sales channel will not double the cost, as one might expect, but rather increase costs perhaps by a factor of 10; it is the increase in complexity that often prevents profitable growth. It is particularly hard to handle the arising complexity because it can occur at different levels, such as in underlying IT systems, in leadership or in communication among team members.

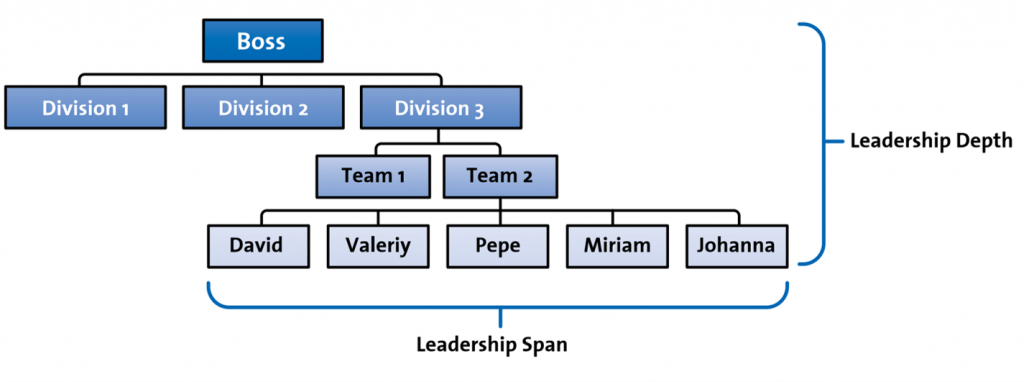

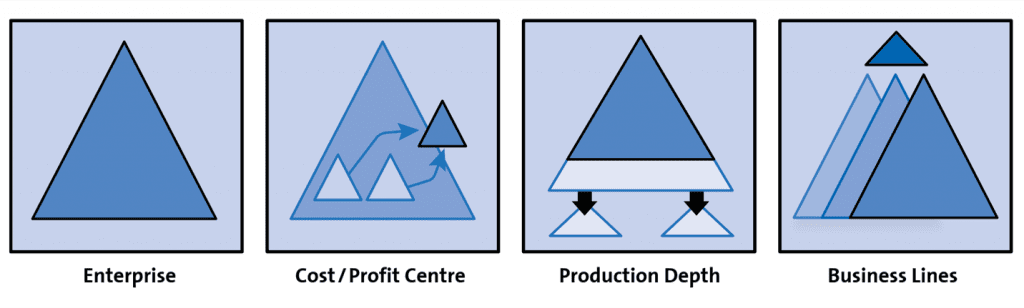

Looking a little deeper into the topic of leadership, it is recognised that growth in a hierarchically organised company goes hand in hand with either extension of the management scope, or an increase in management depth.

By using these levers, a company will undoubtedly encounter natural boundaries.[2] Extending the management scope on one hand increases the burden on the individual executive.

Sooner or later, this leads to a loss of management quality and consequently reduced productivity of each employee.

On the other hand, to avoid wide management scope it is necessary to increase management depth. This often leads to alienation of employees and loss of information in the reporting line.

The situation is aggravated by the fact that the value of many companies is less often increased by the production of simple goods or the provision of repeatable services, but instead by continuously inventing new products and services. Induced by product cycles, leaders must consequently drive the change in logistics, production processes and distribution required by the product. In a large company with tens to hundreds of thousands of employees spread across different offices, time zones, cultures and legal systems, this is a gigantic task. Digitalisation can further aggravate this challenge because of the newly established expectations of speed and accuracy.

The necessary change process in large companies is typically slow and accompanied by compromises and setbacks[3] – often traditional approaches to operational organisation only lead to partial success in change management initiatives.[4]

Digitalisation now offers the opportunity to alleviate many of the problems highlighted above and therefore make companies more robust.

The service orientation inherent in digitalisation helps optimise organisational structures (e.g., new media support in the distribution of information and collaboration in large, split teams).

Complex processes can be improved with digital decision support systems based on big data. Based on these new opportunities, the leadership of staff in the classical sense can increasingly be replaced by collaborative approaches. Ultimately, large enterprises can overcome the limits caused by size and complexity. This means that they can extend their businesses profitably.

The digital world also allows new self-organising and agile teams to appear.

Beyond classical hierarchies, teams must be able to form quickly as the need arises, mirroring the content of the challenge at hand. Such teams are familiar from classical project work, but in contrast to forming such cross-disciplinary project teams top-down, the organisation needs the flexibility to let such teams form themselves bottom-up. Employees must be empowered to aggregate into agile teams, as the need to do so arises. A suitably innovative and collaborative work environment must support such clusters of employees.

_____

[1] Akamatsu, K.: ‘A historical pattern of economic growth in developing countries’, Wiley Online Library, p. 22, 1962.

[2] Kreitz, A., Lindstädt, H., Wolff, M.: ‘Führungsoptimalität versus Organisationsoptimalität von Leitungsspannen: eine modellbasierte Untersuchung‘. In: Kossbiel, H., Spengler, T.: ‘Modellgestützte Personalentscheidungen 10’, Rainer Hampp-Verlag, 2008.

[3] Ryschka, J.: ‘Veränderungen in der Firma – und was wird aus mir?’, Chapter 1, Wiley-Verlag, 2007.

[4] Terpitz, K.: ‘Die Firma ist eine Baustelle’, Das Handelsblatt Online, 2008.