Enterprise Transformation Circle

EnTranCe is a vibrant community of practitioners from various industries who share knowledge and develop creative solutions to the challenges of a new era.

We use our working groups, the Circles, to learn from each other and explore different perspectives. Here, we develop new solutions together that go beyond mere textbook knowledge.

We document many of our results in the form of Best Practices articles, which we make available to the community and all visitors.

The Foundation of the Enterprise Transformation Circle

One of the most read digital textbooks for mastering a new era explains the “why,” “what,” and “how” of business transformation initiatives, delivering various best practices in an easy-to-use way for the big journey to a modern enterprise.

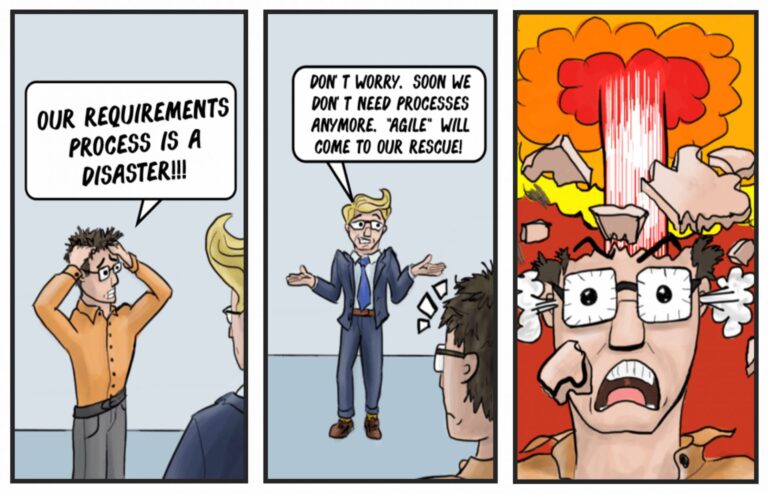

A comprehensive and well-founded article series draws the essential attention to the diverse widespread misunderstandings and drawbacks in regard to the very common implementation of agile practices at the company level.